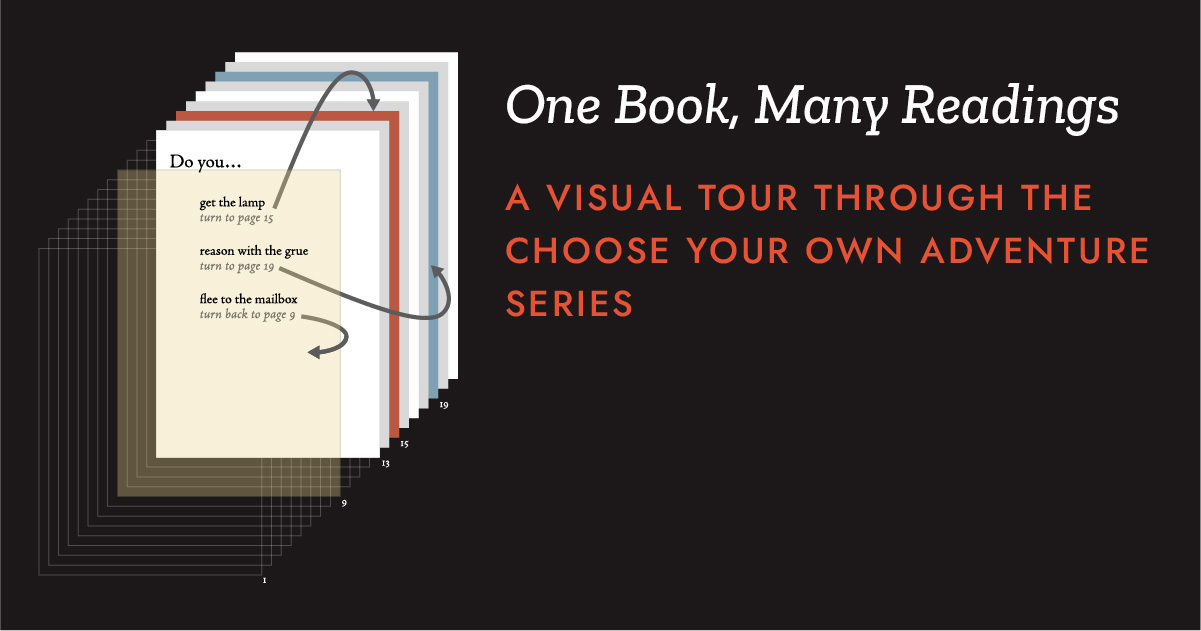

I suspect this similarity to software-style interaction also points to why this kind of book came about when it did. Interactive gamebooks started to appear in the late 70s, around the same time that Interactive Fiction popped into existence with Colossal Cave Adventure (which begat Zork and, in turn, Infocom). Whether in paper or electronic form, these games all hinge upon movement through a set of static locations: pages in the book, or ‘rooms’ in the text adventure. And from any one of these locations you can move to a new one based on a set of fixed rules. The book might offer you the choice of going to page 13 vs 22 while the game lets you choose rooms to the north, west, or south. This sort of locations-and-transitions structure is known in computer science jargon as a finite state machine, a branch of theory an old classmate summed up as ‘flocks of circles and arrows’.

In scanning over the distribution of colors in this plot, one clear pattern is a gradual decline in the number of endings. The earliest books (in the top row) are awash in reds and oranges, with a healthy number of ‘winning’ endings mixed in. Later cyoa books tended to favor a single ‘best’ ending (see CYOA 44 & 53). The most extreme case of this was actually not a Choose Your Own Adventure book at all but a gamebook offshoot of the Zork text adventure series. The Cavern of Doom (labeled WDIDN 3 above) has a virtually linear progression where endings later in the book are increasingly better than those on earlier pages. This is reflected in the nearly unbroken spectrum from red to blue when scanning down the rows.

Another surprising change over time is the decline in the number of choices in the books. The mess of light grey boxes in the top row gives way to books like A New Hope (CYOASW 1) which have more pages devoted to linear narrative than to decisions and endings combined. But to address this apparent pattern with more rigor it would be best to look at the numbers of pages in each category independent of their placement in the book.

It could be that the glut of choices in the early books reflected more a rush toward the new than a well-considered balancing of storytelling and reader-directedness. As the genre developed, the choice-based structure ceased being so novel that it was an experiential end in itself. Perhaps only then could it recede into its proper role as a gameplay mechanic – all the more potent when used judiciously.